Is it ever okay to choose art over family?

Living: My husband's birthday, the literary festival, and the power of art [love]

I wrote this before the hurricane, and now everything feels trivial in comparison. My heart aches to remember Asheville as it was. Though we’re rebuilding—growing stronger and drawing closer together—the loss still sits so heavily that grief sometimes catches me off guard, and I have to cry to release some of the weight. I’m deeply grateful for this time filled with love and art before everything changed; it feels even more precious now.

It was the weekend of my husband’s thirty-eighth birthday, and I had planned a full day just for him. Then, I remembered the literary festival taking place that same weekend, with the main event scheduled for the evening of his birthday. I had heard about it weeks earlier but had forgotten until I saw a post from a poet I’d just started following on Instagram announcing her reading there.

Recently, I had the chance to stay at the Hemlock House for an artist residency where I arrived without any specific intentions—partly because I needed rest and wanted to be open to whatever inspirations might arise. Since motherhood, I don’t have the sort of life where I have the space to sit and wait for inspiration. When I write, I need to have a clear goal; otherwise, it feels like I’m just wasting time. But the other part of me felt scared to go with a goal and not be able to meet it. What if I squandered it?

While there, the host shared a book of poems by RK Fauth, who had just stayed there. I read her book, A Dream in Which I Am Playing with Bees, to distract myself from my own writing, and followed her on Instagram. That's how I saw the festival flyer on her feed. I mentioned it to my husband, and he said I should go. “We can celebrate my birthday any day. You can't just reschedule the literary festival.” He laughed his warm, understanding laugh, and though I felt a twinge of guilt, his support was unwavering. I purchased the full pass for the festival, which included the night before and the night of his birthday.

The first evening featured rapid readings from sixteen authors, mixing poetry and prose. I drove out to the city alone after kissing my husband, kissing my son, kissing my dogs. I parked in a shitty lot at the bottom of the hill because downtown was a madhouse. Was it always like this on a Friday night? Usually, I’m tucking my toddler into bed at this time, then sitting in front of my red light, trying to meditate through the day’s triggers still buzzing in my nervous system.

As I walked to the theater, a rare feeling washed over me. I hesitate to use the word “unburdened,” but that was exactly it. For a brief moment, I walked free from the weight of motherhood and marriage, from the demands of all those who loved me and my own pressing need to be enough for them.

I found a seat near the front-middle with no one on either side of me. The writers emerged one by one, each reading in quick succession. The array of voices, stories, and metaphors unfolded—just as I began to fully grasp one piece, wrapping my heart around the words, another poet would begin, introducing a new rhythm, tone, and emotional center. I expanded in every sense; my entire being stretched to carry it all.

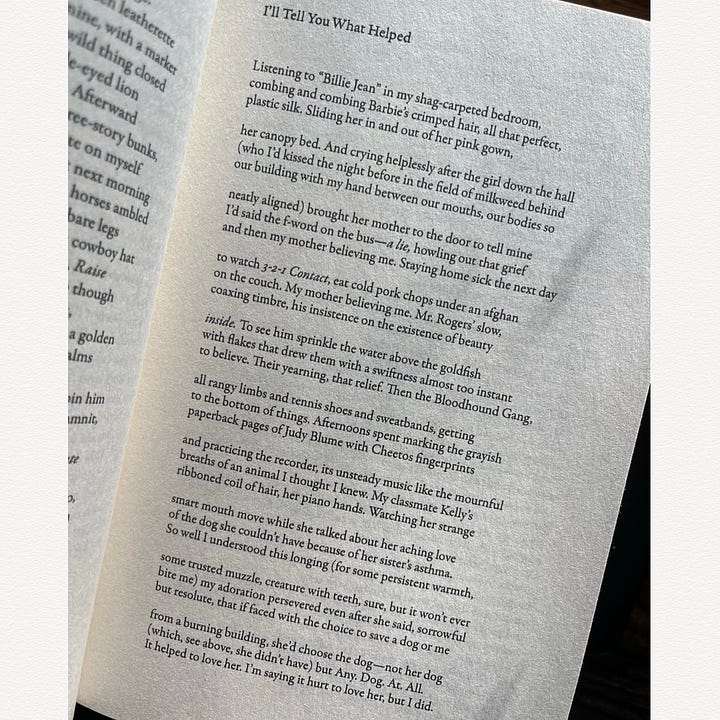

I cried when Melissa Crowe—a poet I had never read before—read a piece titled “Dear Life.” She revealed that she wrote it as her marriage was unknowingly unraveling—the poems, it seemed, knew before she did and they gently showed her the way out.

Goddamn, art is powerful.

Tears rolled down my face as I thought about how free she must feel now—how free she must BE now. I'm learning to be free too, nurtured by the love that bursts from my life: each good morning, mama, my husband’s lingering hugs in the kitchen, hands forever reaching for me, grazing flesh, kisses goodbye and goodnight and for no reason at all. I used to run from this love, afraid that if I wasn't ready to be the first to leave, I would be the one who’d be left.

I've been left many times, mostly by my mother, and even by my father, though it was I who convinced him to leave. Each leaving has hurt more than the last. My mother would argue it wasn’t her choice to leave, that she was taken—arrested more times than I can count or remember—and maybe she'd be right. But all I know is that her life never seemed to lead back to mine, and it always felt like she was the one doing the leaving.

During the reading, I’d made a list of the readers and drew stars next to the ones who made me cry or clutch my heart or lose myself entirely. Afterward, I wandered downtown, picking up a stout-infused chocolate cake for my husband’s birthday and a cardamom and pistachio chocolate torte for myself, which I savored slowly at a café table outside. The streets were loud and full and for a moment I felt like I was in Paris. I wished I’d ordered an espresso even though it always made my anxiety worse.

Street music filled the space between the sound of cars zooming by and the fleeting conversations walking past. I continued to immerse myself in language and lives other than my own. By the time I made my way back to the bottom of the hill, the city was still very much awake, but I was yawning, facing a dark thirty-minute drive back through winding mountain roads.

I pulled up to our house, where my husband had turned on the string lights we’d repurposed from our wedding. I stashed the cake in the back of the fridge and tiptoed up the stairs, careful not to wake the dogs—who would undoubtedly wake the baby who I guess is not really a baby at all anymore. He’s a kid now as he likes to tell me. He’s three, though I remind him he’ll always be my baby, which always brings me a smile.

The moment I opened the bedroom door, the dogs greeted me with gentle nudges of their soft, black snouts. My husband embraced me, asking how it went. He settled back on our king-sized bed, our chihuahua curling up beside him, and I stood in the middle of our bedroom, too excited to sit or undress, recounting everything I could remember. And he listened, absorbed in every detail.

He would have loved to join me if he hadn’t needed to stay home with our son. Our lives are now a delicate balance between parenthood and art—only, it's not a balance at all. If asked about the hardest part of motherhood, I'd say it's this: feeling perpetually split between two worlds—my family and my art. I want to give all of myself to both, yet I can't, and someone or something is always left unsatisfied—most of all, me. I empty myself, and yet it never feels like enough. My son and my husband deserve more, and so does my writing—so do I.

I thought the tug-of-war between these worlds would ease as my son grew older, but it hasn't. He's so full of life, so free, that I can’t bear to miss a moment of his joy. Yet, when I'm not writing, I feel lost. While motherhood fills me with immense purpose, the absence of writing leaves me feeling restless. It’s as though I can’t fully immerse myself in one without the other. I need to do both, BE both—a mother and a writer—and yet, I struggle to blend these worlds, or perhaps they are too intertwined, which is why it feels like I can never get anything done.

The next morning, I was still buzzing from the previous night's readings, with a full day of literary events planned. The schedule was packed with readings, talks, workshops, and a book fair, culminating in an onstage interview with one of my favorite authors, Lauren Groff. However, I just couldn’t pretend it wasn’t my husband’s birthday. I found myself splitting in two once more, trying to juggle the festival's schedule while planning to weave in moments to celebrate him. I was determined to be present for him, however brief.

Earlier that morning, my mom brought over a plastic Blue’s Clues guitar for my son, which played annoyingly incessant songs, making it hard to think. I had hoped we’d start the day by getting coffee or breakfast together, focusing on celebrating my husband, but by the time we finally left the house, it was too late for any of that. It’s amazing how much time my toddler and husband can take to get ready. I heard my husband's beard trimmer buzzing and settled in because I knew we weren't going anywhere anytime soon. Meanwhile, my son took an hour to eat a tiny bowl of oatmeal, barely able to sit still long enough to take a bite. I surrendered to the snail’s pace and made peace with missing most of the morning's festival events.

When we finally left the house, it was too late for the workshops I had planned to attend, but I managed to make it to the book fair. Meanwhile, Pride Fest was in full swing downtown, right next to the theater. The streets were alive with rainbows and glitter and joy, and I felt a pull to be outside celebrating.

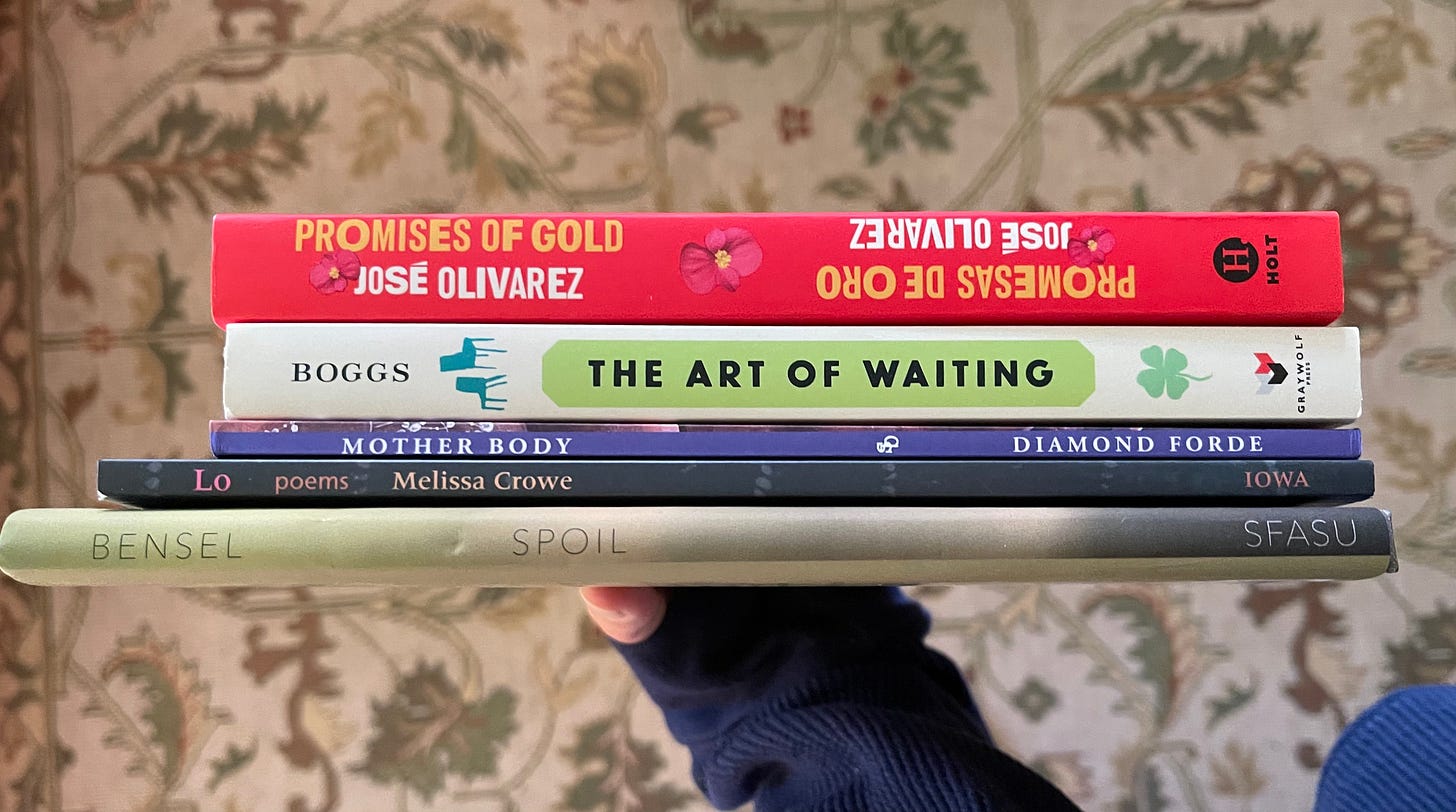

At the book fair, I poured over the works of authors I had heard the previous night, buying more books than my bag could hold. I wandered around the booths—most of them literary journals, small independent poetry presses, and MFA programs. I paused by the Warren Wilson table to dream about getting an MFA. They asked me if I was interested, but I shied away from the question because who was I kidding? I could never make it work. I don’t have the money or the time. I took a flyer, shoved it into one of the books I bought, and slinked off.

I met up with my family and wandered over to the Pride Fest to watch the drag show in the sunshine and drink a Matcha lemonade from some kind of compostable bag. We strolled through the festival, waving rainbow flags, with our son munching on a rainbow croissant and sporting a new hat that said “Love” in rainbow colors. We made glitter crafts in the grass until our hands and faces sparkled, then grabbed Indian takeout from our favorite place that had bad ambiance but good food, and ate while watching the love in the streets.

After eating, we walked to the dim café with the good vibes and talked about love, life, and art over drinks while our son strummed pretend tunes on his Blue’s Clues guitar—now silent, as we had removed the batteries. I tried to stay present because it felt special to be sitting there in a beautiful café across from my beautiful husband and our beautiful son after all these years of doing life together. Yet, part of me still yearned to be back in the dark theater, listening to others pour out their hearts.

Split between two worlds. Could I one day blend the two? Will my son join me at events like this, or will he dismiss them as boring? I read poems to him every day and tell him stories every night, hoping to instill in him an appreciation for language. This way, he might one day sit on the edge of his seat, clutching his heart as he hangs on to every word spoken by people brave enough to share their souls. Only time will tell. For now, he has his joy, his plastic guitar, and the crunch of peanut butter pretzels he munches in my ear. I tell my husband I'll need to leave them at four to catch a poetry session at the theater.

We walked together up the hill, sharing a kiss at a stoplight before heading in opposite directions. I felt a pull toward them. Was the poetry reading really going to be worth it? Would it offer anything different from what I had heard the previous night? Shouldn’t I spend the rest of the evening with my family, enjoying the last of the sunlight, maybe grabbing a light dinner together before parting ways for Lauren Groff? Standing on the sidewalk, I watched my husband and son walk away. I had already missed the rest of the day's events, struggling not just with being in two places at once but with choosing art over my family.

Why do I have to choose? Is it choosing?

I stayed the course to the theater and felt guilt swirl in my chest, but I needed this. I needed to get comfortable with sometimes prioritizing my art, my writing, and my own desires if I was ever to live the life I dreamed—a life where I could write, engage actively in the literary community, be a mother and a wife, be everything—maybe just not all at once, but everything just the same. Could it all coexist? I needed to believe it could, and so I went to the poetry reading.

Melissa Crowe was reading again, and I was eager to hear more of her work which had moved me to tears the night before. After her reading, I told her how powerful her poem had been, and she thanked me, asking if I wrote poetry myself. I responded with a hesitant no, not really, which was the truth. I mentioned that I had written a memoir but then added, “But yeah, I mean, I'm not a real writer.” Downplaying my work and playing small are my favorite limiting beliefs to live out. Melissa was encouraging, a trait common among writers who have been in the trenches of the craft and made it to the other side. They've seen the light at the end of the tunnel and are here to tell you to keep going.

After the reading, I said my goodbyes and realized I had almost two hours to spare before Lauren Groff’s session. I wandered to a Japanese steakhouse and got a table for one—something I hadn’t done since my days in Los Angeles. It felt good to sit alone, without the need to make conversation or stop my toddler from eating the salt. I ordered a Japanese sweet potato with miso butter and brown sugar along with an heirloom tomato salad with peaches, charred tofu, serrano peppers, and a Japanese herb whose name escapes me.

As I ate, I immersed myself in Melissa Crowe’s poetry collection, Lo, and jotted down notes about the readings in my notebook. I kept looking around to make sure the restaurant still had tables—I felt bad taking up space. I hadn’t finished my food, but when the waiter had come around again I told him he could bring the check. He gave me a puzzled look, noticing my half-full plate.

“I feel bad taking up a table,” I said.

“Take your time,” he said. “Relax. You’re vibing here with your book and your journaling. There’s no rush.”

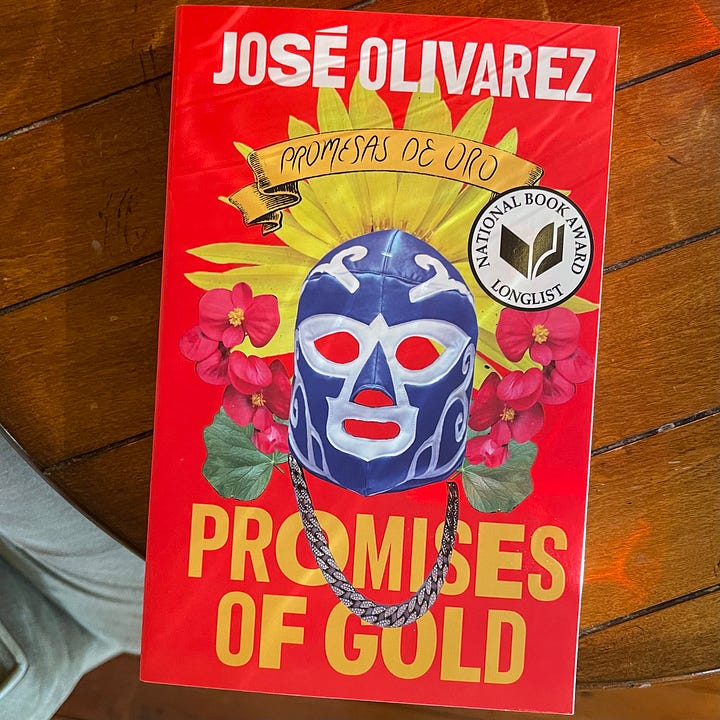

I let out a breath I didn’t realize I’d been holding and relaxed into my seat. I reopened the book and continued reading poems, savoring each bite of peaches while letting the language sink in. When I was ready, I paid the bill and headed back to the theater, arriving with ten minutes to spare. Finding a seat near the middle, I was excited to learn there would be another poetry reading before Lauren Groff’s session. This time it was only two poets—Diamond Forde and José Olivarez—and, once again, I found myself in tears by the end.

Diamond set the tone for the evening in a way I had never experienced before. She clearly outlined what she expected from us as listeners, emphasizing that she didn’t want to perform for a sea of dark silence. If something resonated with us, she wanted to feel our response. She guided us through an exercise, asking us to imagine a bowl of our favorite food, and then prompted us to take a bite. “What sound do you make?” she said. We all responded with a collective, “Mmmm,” and she said that’s right—that’s what she wanted to hear.

She encouraged us to break free from the hesitation that often keeps people silent, inviting us to snap our fingers, pat our chests, stomp our feet—whatever it took to make some motherfucking noise and express what we felt. She didn’t say motherfucking, but she should have because we were all pretty riled by then and ready to make her feel heard in every way possible. It was a refreshing and deeply honest way to start a reading, immediately drawing in not only our minds but our hearts and bodies too, before she even spoke a word of her poetry.

I was mmming, snapping, stomping, and clutching my chest through Diamond’s entire reading. I loved the rhythm of her voice and the way she made me not only inhabit her body but mine as well. Her poetry, which centers on the wonder and magic (and sometimes pain) of the female body, gave me permission to take up space, and to feel that my needs and longings mattered.

As a woman who’s spent much of her life feeling invisible—not just to society, but even to my own parents—I had buried my needs so deep that I couldn't even articulate what I wanted. When someone would ask me what I needed, I was at a loss because I’d never thought about it. I wasn’t used to making space for those thoughts—especially not when it came to my emotional or physical needs. Asking for what I needed felt impossible, so I shrank and I settled and I kept my mouth shut. But Diamond’s poetry made me want to stretch out my arms and shout—to ask for what I want and expect it.

She reminded me that we are allowed to express our needs, our wants, our expectations—our bodies. I’m still learning how to live in my body, how to feel that it even exists. When my therapist asked me, “Where do you feel that in your body?” I said, “What body?” because I felt like a floating head—disconnected. But Diamond’s words brought me into my body, into my heart, and they empowered me to listen to my needs in a way I hadn’t before. So, as you can imagine, I made some motherfucking noise.

At one point, she had the entire audience singing along to the chorus of “Jolene” by Dolly Parton, and the sheer sense of community in that moment hit me hard. There’s something so powerful about music and poetry coming together. Poetry, in itself, often feels like music, and maybe that’s why I’m so drawn to it. Music being my first love and all.

When José Olivarez took the stage, we were primed, but not fully prepared for the depth he was about to bring. As a first-generation Mexican-American, José’s poetry is steeped in the experiences of his family and heritage. His poems seamlessly shift between joy and sorrow, blending hyperbole with deeply personal stories, all while holding space for the complexities of identity. I could feel the expansiveness of his work—creating room for stories, for reflection, for community, and for joy, even amid hardship. It’s the kind of joy I feel most at home with—the kind that exists within (and despite) the challenges.

If I had to choose one word to describe José, it would be joy, because it radiated from him like a light. There was a genuine, almost giddy excitement as he stood there, reading his poems—not an ounce of pretense or inflated ego, just pure gratitude for being able to share his work. I hung on every word. Listening to him felt like coming home—it reminded me of the Mojave and my childhood in a mostly Spanish-speaking town, where I fell in love with every dark-eyed, dark-haired boy who called me mija. I have to admit, I fell a little bit in love with him. The way he effortlessly slipped between Spanish and English, the way he wrote about his family with such openness, covering the full emotional spectrum in every poem. Touching on everything from gentrification and immigration to cheese fries and therapy and love—it all felt so full of heart, and I felt every word.

When I got home that night, I climbed into bed next to my husband, and we stayed up until midnight watching YouTube videos of José reading poems because clearly, I hadn’t had enough. I’ll leave you with one of my favorites...

Funny how I set out writing this, fully intending to talk about Lauren Groff, but here we are, almost 4,000 words later, and I still haven’t even touched on her talk (Why am I like this?). That will have to wait for another time because there’s still so much I want to say—about her, her writing process, and the way she’s impacted my life. Stay tuned for that in a future post. For now, I think I’m still navigating how to blend the worlds of family and art—how to be both mother and writer, to show my son that dreams are worth fighting for, and that love is too. Will it always feel this hard?

Thank you for sharing this experience. As a mother also, I applaud you for not giving up on your art. I also must say how impressed I am with your husband's support of you. How lovely to see that partnership in service of your soul.

You’re already doing it- you do it all the time. I reckon it will always be hard but the hard changes and takes on different forms.

That’s been one of my greatest takeaways from parenting- the hard changes/it’s always hard, but similarly the magic shifts and grows and becomes more magical, I think.