When grief is wrapped up in a good thing (July wrap-up)

The heavy sun of a midwest summer, the patterns of grief, and why sometimes waiting it the only thing we can do

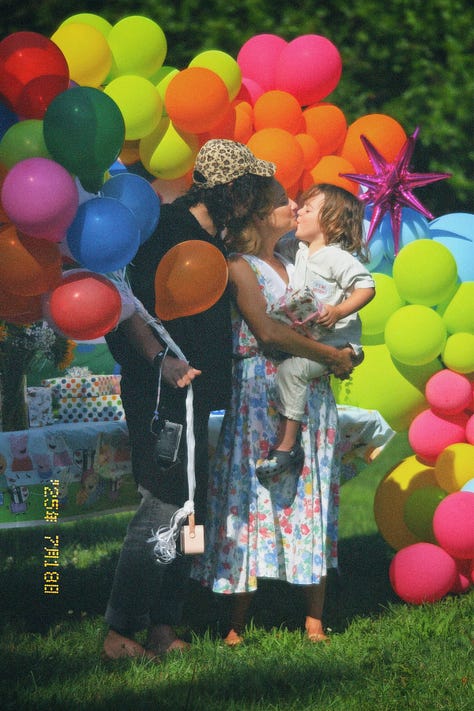

July was the heavy summer sun and my son’s fourth birthday. It was sunflower bouquets and rainbow balloons and pizza too many nights of the week. It was fireflies and campfire sparks and fireworks from the shoreline. It was sunset swims where the sun dipped below the horizon and filling our pockets with beach glass. It was birdsong and gold mornings and crying over poems at the faded picnic table under the walnut trees. It was the first tomato on the vine and tree-ripened peaches and too-hot salsa that we ate anyway. It was stacks and stacks of kid art, flower petal potions, and notebooks full of stories my son wrote. It was full moon rituals with the kids and running through a thunderstorm and the deer in the vineyard. It was writing circles and old photo albums and my Grandma’s frail frame in my arms during a goodbye hug. It was holding other people’s responsibilities as if they were my own and still learning what it means to keep a boundary. It was pages upon pages of pressed wildflowers, each from a different day, holding a different meaning, some from my son, some from my brother’s daughters, some from my husband. It was stomachaches in the middle of the night and losing all the rhythms that make me feel grounded. It was the passing of Andrea Gibson, passing of my cousin, passing of the children, so many children. It was fields of blue cornflowers, blue lake water, blue-firefly-dark, blue Michigan sky, and the indigo bunting. Blue, blue, magic blue and sorrow blue, blue of longing, blue of loss. It was the sound of the sandhill cranes in the swamp and a sink full of dirty dishes and grief I couldn’t shake. It was used book stores and my father’s reading voice like a balm. It was slow rivers and roadside fruit stands and the wet air of a midwest summer. It was feeling some big shifts and at the same time feeling like I’m not in a place to make them. It was the Chicago skyline and the birthday donut with rainbow sprinkles and pushing my son on the swings in the cities last light at the exact moment he was born four years ago. It was being so tired and so lost and so sad I could cry but never actually crying and instead, carrying around all that watery grief like a stone. It was my son’s big hugs a million times a day and his kisses on my shoulders, my cheeks, my nose, my lips like a blessing. It was the tangerine sky after a rain and running through the grapevines to catch the bounty. It was waiting and resisting the waiting and having to wait anyway.

I’m writing to you from the car again, just like last month’s wrap-up. Only this time, we’re winding our way back to the mountains, blue as breath, where home waits in North Carolina.

I’ve been in Michigan for the past month, split between my dad and my brother, both tucked about twenty minutes from Lake Michigan in different directions. I go every summer, and every summer, I fall more in love with the lake. For the hush of it. For the way the fireflies string themselves like lanterns along the dunes. Every summer I say, maybe I’ll stay. I scroll Zillow like a prayer. But then I leave, again, and start the cycle over next year. Maybe one day something will reveal itself at the perfect time.

It’s only been a month, but it feels like a whole lifetime has opened and closed inside of it. I’m wrung out. Whatever life I arrived with has been squeezed to the corners. I’m hanging on the line, damp and heavy, waiting for either sun or storm, I’m not sure which.

This trip was meant to be an intentional pause. A stretch of joy. A return to play and presence and creativity. And it was. Until it wasn’t. It was also disruption. A kind of unraveling. The momentum I’d been gathering all spring got scattered by other people’s schedules and moods and needs and whims. All my rituals, my rhythms, my anchors, went missing. Yoga, writing, meditation, stillness, therapy, sleep—I let them slip, even as I watched them go. And in the absence, I realized, maybe I do need a lot to stay steady. Or maybe I don’t. Maybe I just needed to hold firm with one of those things and that would’ve been enough. It’s hard to know which truth to trust. All I know is that I’m glad to be going home to the quiet and the slowness and clear auras of the little family that is mine. Where we all move together with love and ease. Where I can sleep in my king-sized bed after kissing my son goodnight, and wake to a clean house filled with silence and space.

I love my brother and his family and I love my dad and his wife, but weaving yourself into someone else’s lifestyle and parenting style and philosophies and beliefs and energy fields is hard. It’s a tender kind of disorientation. I get sucked into the vortex of a life that’s not even mine. I want to help and to fix and reroute their patterns and say, really, why can’t we all just be happy and grateful and stop making things harder than they need to be?

But people have to come to their own peace. They have to stumble through the fire, find their own path out. I know this. And still, I’m tired and drained and I wish I could sleep for a week. I feel untethered. Lost. I’m not sure if it’s their energy clinging to mine or if something deeper is shifting in me. Either way, I need time. Sometimes waiting is the hardest part, but it’s necessary. The only way, really, unless you want to blow everything up and double back on yourself, which I don’t. I’ve done that too many times to count. These days, I’ve learned to wait. To let the film lift, to let the emotional wave pass, and see what remains in the stillness. That’s where I come home to myself. That’s where I find clarity. That’s where I make decisions now.

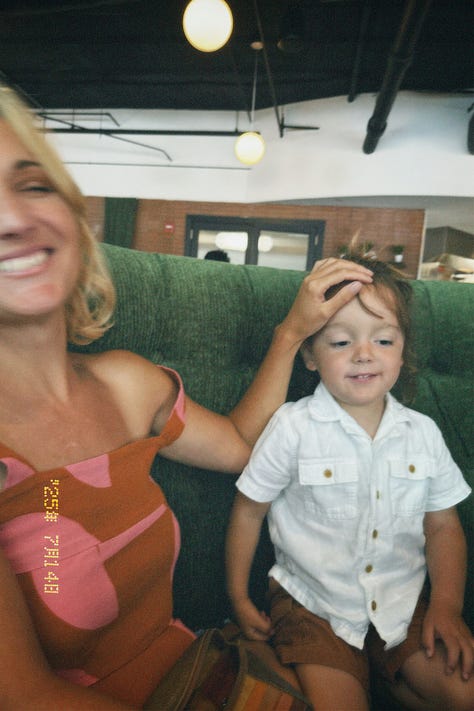

This last month, my son turned four and that carried with it a swirl of conflicting emotions, grief and joy and celebration and longing and nostalgia. I love watching our family gather around him like a campfire. But there’s this ache I carry for the baby he once was. For the rhythm of his breath against my chest, the soft weight of him in my arms. That ache lives beside my love for who he is now. Both things true. That’s motherhood, I think. Holding everything at once. The joy, the grief, the impossibility of time.

He’s buckled into the backseat now, in a green outfit patterned with alligators in sunglasses, listening to Peppa Pig and watching the road with those sparkle-eyes of his. As cheesy as it sounds, I feel like the luckiest mother alive. He is all kindness and curiosity, all magic and love and wide-eyed wonder. I love traveling with him. Driving up and down and across this country just like my grandparents did with me when I was little. Noticing, noticing, noticing, and steeped in gratitude for simply being alive and wow, look how green the trees are.

I fell in love with life from the backseat of a wine-colored Oldsmobile with velvet interior, looking out the window, counting willow trees and singing songs and learning about the world through the lens of my grandparents. I hope I’m giving that same gift to him. Only he’s more in love with the cities and their ornate architecture and bridges and rail systems while I’ll always be chasing trees and birds and the shape of light. The blue water and blue sky and the time of day where the sun dips below the horizon. Together, we make a good team, catching the world like raindrops on open palms.

My grandpa who always did the driving has passed now, and I swear there’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think of him. He’s in everything, especially the trees which he knew by name and the red winged blackbird that he pointed out on every road-trip through the midwest. He taught me the state capitals from the front seat, reciting them like scripture. Same with my multiplication tables. Most of what I know about anything comes from him.

He was a principal, a missionary, a house-builder. He wrote sermons in longhand on yellow legal pads and read books like they were oxygen. He planted, pruned, and harvested fruit trees like the fate of the world depended on it. He was a master whistler, hiker, birder, storyteller. He could read aloud for hours, his voice rising and falling like wind through leaves. But he couldn’t cook to save his life. Could barely toast bread, never mind boil water. He ate raw oats with cold water like it was some kind of frontier delicacy. I used to type his sermons into the old computer, the yellow pad in his big hands. He’d read, and I’d type as he spoke.

Why am I telling you this? I don’t know. Maybe because while I was up in Michigan, I went back to his house on the hill. The one where two ponds sit like mirrors in the valley, surrounded by cattails and the ghosts of those fruit trees he loved. I went to see my grandma, who shaped me in equal measure. Everything I know about how to make a home, how to cook, how to move through a brutal and beautiful world without letting it break you. How to make a meal, a moment, mean something, all comes from her. She was so frail this time I was afraid to hug her. Still, she lives in that same house, once echoing with my grandpa’s big, infectious laugh. Now it’s just her and my aunt, their bubble shrinking by the year. But still, they have each other. And in this world, that’s no small thing.

When I was leaving, I hugged my aunt and told her to take care of Grandma. Three days later, she called to say that her only daughter (my cousin) had been murdered. There was a dark story attached to it, and for days I felt sick with grief. Grief for my aunt. For my grandma—85 years old and now grieving another one of her children. Will it ever end? Grief for my cousin, for the brutality she must have endured. I couldn’t shake the images. The thoughts. I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t write, couldn’t meditate or eat or think straight.

Then, a few days later, another call came. It wasn’t murder, they said. It was suicide. Where did the murder story come from, then? How did we get here? No one seemed to know. No one could give me a clear answer. I had to let it go. All I know is, she’s gone.

I grew up with her. When I lived in that shitty house with the meth lab in the garage on a forgotten corner of the Mojave Desert, her mother used to bring her up to play with us. Sometimes she’d take us to church and afterward treat us to a Happy Meal, which felt like the height of luxury. We never got things like that with Dad. She’d straighten the house, do what she could, check in on what remained of her brother.

Their other brother (my uncle) died in a car crash with my dad when they were in their twenties. After that, it was just the two of them left. Just each other and their bad choices. My dad married my mom, who was a disaster, and she unraveled what was left of his life. My aunt married a controlling alcoholic who verbally and physically abused her, threw her onto a glass table in front of her daughter when she was just a child.

I guess when you live your whole life shrouded in grief, you stop looking for the exit. You forget to ask if there even is one. Grief becomes the air. The backdrop. The hum beneath everything. You don’t make choices that lead you out. You make the ones that hold you in place. That feel familiar. That don’t ask anything too new of you. You trade one sorrow for another, thinking this one will hurt less, this one you can control. But it’s the same note, just played in a different key. It still ends in loss.

We have this way of making homes out of patterns, especially the ones that wound us. Pain, when it’s predictable, can feel like safety. A story repeated becomes a kind of comfort. We pick the ache we recognize. We build whole lives around it. And sometimes, I think, the grief gets hungry. It wants new language. A new shape to live in. So you enter a relationship that will fail, or a house that will collapse, or a life that was never yours to begin with just to keep the sorrow breathing. Just to keep it moving through you like blood.

We like to think healing is linear. That the moment you see the truth, you walk away from the flame. But it’s not like that. Sometimes you stare straight into the fire, and then you walk in anyway. Because you know the heat. It reminds you of something, and part of you still believes you can stand it.

That’s what I saw in my aunt. In my dad. In the whole broken constellation of people I come from. They weren’t chasing joy. They were keeping grief on a leash, calling it love, calling it home, calling it fate. And I get it. I really do. Because when grief is all you've ever known, you stop trying to escape it. You fluff the pillow and lie down.

I wish I had a beautiful, sun-soaked summer wrap-up for you. Something soft. Something sweet. But grief has been coursing through the world like a thief lately. Stealing presence, stealing joy. It’s everywhere. In the headlines, in the air, in my own family. So here we are.

Besides my son’s birthday, there was one bright spot I kept turning over in my hands like a gift. A day with my dad. He took off work, planned something just for us, unprompted, unexpected. It might seem like a small thing, but it meant a lot to me. To be thought of, planned around, prioritized. This is not the kind of treatment I’m used to, especially from my father. I thought maybe it would be a car museum or something he loved, and I’d smile and be grateful because spending the day with him would’ve been enough. But he kept the destination a secret, wouldn’t even let me peek at the GPS. We drove through back roads the whole way, tree tunnels and canopies of green, blue cornflowers and Queen Anne’s lace dotting the edges of the fields. Water scrolling by on either side, lake after lake of blue stillness.

We talked the whole way about life, the life we were handed, and the life we chose. We talked about the past and love and how no matter what’s happened, it’s always been the four of us— me, him, my brother, and my mom. Woven together through it all, flawed, but fully accepting of each other. The kind of love that can’t fully be explained, but just is. I steered clear of politics because we don’t always see eye to eye, but we did talk about how heavy and heartbreaking the world can be, and how all we’re really trying to do is hold on to the good parts.

Before we knew it, we pulled into a small town. I can’t remember the name now, but I know it had “lake” in it somewhere. We parked on Main Street and walked a few blocks. I didn’t know what I was supposed to be looking for, but I was looking anyway. And then I saw it. A bookstore. It might sound like a simple thing, but I can tell you that it wasn’t. Not to me. Dad said it was the second-largest bookstore in Michigan. He’d wanted to take me to the biggest one, but that was in Detroit—four hours away. “Maybe next time,” he said. But this was more than enough. This was everything.

As soon as we stepped inside, I made a beeline for the memoir section. Dad followed. Within ten minutes, I had a stack so heavy my arms ached. He wandered off to the fantasy shelves, searching for a series he used to read with his dad—my grandfather, the same man who taught me most of what I know. And taught him, too. Dad poured himself into books until he met my mom, and everything changed. He never really found his way back, but still, I got the reading bug from him. So at least there’s that. Dad pulled books off the shelves and read me passages, just like Grandpa used to. I see more of him in Dad every day. And truly, there’s nothing quite like a smooth, deep voice reading aloud to you.

The first book I grabbed was How to Write an Autobiographical Novel by

—a title that’s been on my list for ages, and finally found me at the perfect time. I picked up a signed first edition of The Maytrees by Annie Dillard, and a book of essays by Barbara Kingsolver, who I’ve loved ever since Demon Copperhead. I looked for Patti Smith’s M Train. I’m always scanning the shelves for that one in used bookstores. Like Alexander’s book, I know it’ll show up when I’m ready for it. I skipped the poetry section entirely as I already had too many books in my stack. On the way out, we sifted through the free book stall out front, and I found a copy of Joan Didion’s A Book of Common Prayer. What a find.Afterward, Dad took me to a little café that sat at the edge of a river. We sat side by side, eating chocolate muffins and drinking coffee, watching the water move slow and steady, like it had nowhere else to be. He told me about his work. How he bends steel, cuts it and lasers it, programs the machine just right. How the shop gets hot and loud, and his legs ache from standing all day. “But it’s honest work,” he said. “It’s honest work.” He said it twice. Like maybe he needed to believe it. Like maybe I did, too.

Because it’s a long way from the meth lab he built in the garage. Honest wasn’t a word any of us used back then. It wasn’t about truth. It was about getting by. Surviving. And maybe, in some ways, it still is. But that’s the pattern I’m trying to break. I don’t want just the getting by. I want the truth even if it’s heavier to hold. I want the small moments that are actually the big ones, the ones that shape a life, if you stay with them long enough to really see what they’re trying to show you, really see them for what they are.

That’s how I feel about everything lately. You have to look at it. Not glance, not rush past, but really look. That’s the only way you know what it is. That’s the only way you know what matters. Grief taught me that. Or maybe it just made me ready to learn. To stop numbing, stop running, and actually stand still long enough to witness what’s here. The weight and the beauty and the longing. The small, shimmering miracle of being alive at all.

And maybe that’s what I’m learning this summer. That grief doesn’t always come crashing in. Sometimes it slips in quietly, wrapped inside the good things. Sometimes it arrives in the shape of your father in a used bookstore, or your son’s fourth birthday party, or a phone call on an ordinary morning.

Sometimes, grief looks like love just trying to stay a little longer.

I love you my dear. I know these lessons have been hard to learn, and you probably wouldn’t have chosen to learn all of them if you had been given the choice ahead of time. But the understanding and the ability to see life for what it really is in the bad AND the good, and your ability to share that with others—that has more of an impact than you know 🫂❤️

From top to bottom, this was beautiful. And I related to so much of it.