In the Waiting Place, Where Joy and Grief Sit Side by Side (April Wrap-Up)

How many times can a heart break?

*You’ll probably hear cars passing outside, the washer humming, my dog stretching, and a little sleep still in my voice, but here I am, reading it to you anyway.

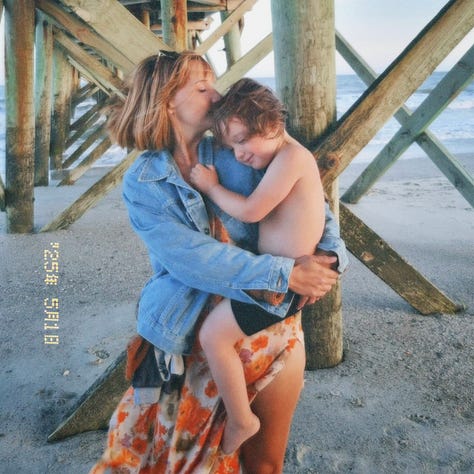

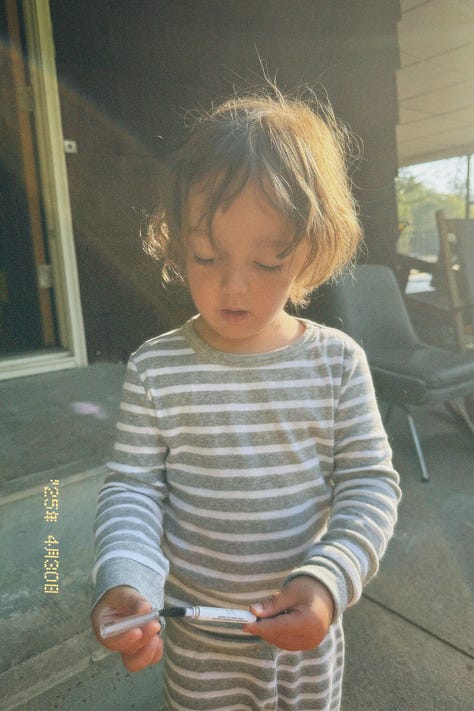

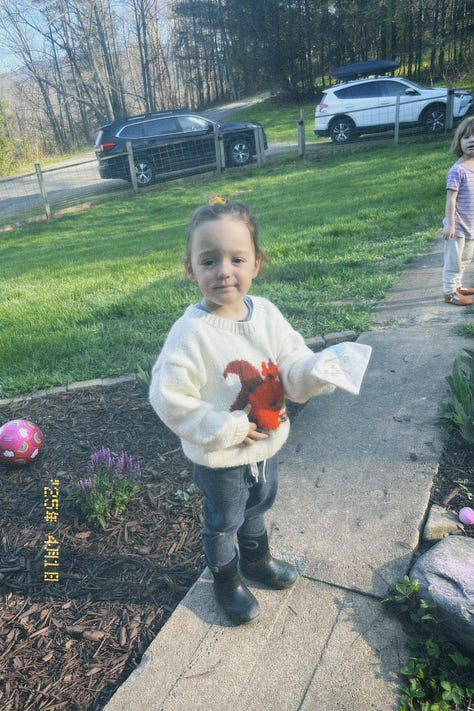

April was standing at grief’s threshold again, watching over my mother in the hospital bed and wondering if either of us would make it back to ourselves. It was Easter eggs the color of the ocean and trampoline sunshine and my son’s first haircut. It was watermelon dripping down our chins and the bloom of the peach amaryllis. It was hugs from my ninety-five-year-old grandmother who still remembers my name, but not my son’s, even though he’s named after her husband. It was lake walks and the artist’s way and realizing I’m already mostly living the life I dreamed of. It was saunas under the full moon and throwing my fears into the fire. It was flowering trees, wrapping birthday presents, and for the first time since my son was born, the quiet thrill of feeling momentum in my writing again. It was hibiscus and gin and running through rain puddles. It was homemade Parisian gnocchi and my son’s Earth Day altar full of wildflowers. It was weaving gratitude into our days by dancing with my son every time something good happened and realizing just how easy it can be to celebrate joy when we let it move through us. It was family visiting from England and from California and going through old film photos in the living room. It was the whiplash of my mom and my son smearing chocolate on each other’s faces, laughing in the kitchen and the next day, she was in a coma after a sudden cardiac arrest. It was my father’s voice breaking on the phone when I told him what happened and long hospital hallways to no answers. It was holding good and bad news in the same breath and feeling trapped by my mother’s choices for the millionth time. It was baby bok choy risotto and slow walks through the botanical gardens, sandwiched between ICU waiting rooms and hospital vending machines. It was my mom waking up but not holding onto her memories and wondering what life would look like for us now. It was driving the long road to the coast and giving my grief to the salt and the sea. It was the Spanish moss and the blue heron in the marsh and finding joy in the sun and my son. It was seashells and sandcastles and seagulls and the ache of always having to leave the ocean.

Time is moving like a riptide—fast, forceful, pulling me under before I can catch my breath. Blink, and I miss whole days. Especially this year, which feels like it’s been dissolving before my eyes. Maybe it’s because I’m trying to do too much. Be a good mother. Run a business. Write. Grow my Substack. And by grow, I don’t mean numbers. I mean finding the people who are meant to be here. The readers who feel seen in the story I’m sharing. And the writers who are brave enough to tell the truth of their lives in hopes that naming it might set them free.

I’ve had a revolving door of guests this month—my brother and his family, then my cousin and uncle from England. I love hosting. I love watching my son light up around his people, his joy filling the whole room. But when you’re living alongside temporary visitors, time compresses. There’s no space to pause, no quiet to catch up with yourself. You’re doing, moving, holding. And then they leave, and the silence echoes. My son lies on the living room floor by the record player, no longer building elaborate worlds with his cousins. The house feels too still.

There wasn’t much room for breath this month. I went to a full moon circle. I celebrated a friend’s birthday. I went to the lake, the river, and the other river in the next town over. I planted sunflowers and picked wildflowers and watched the irises bloom. I thrifted too many times. I went to therapy, and then I went again. I kept moving. But underneath it all, I was avoiding the thing I still haven’t fully processed—my mom had another cardiac arrest. Six years after the last one. She was in a coma for two days. She woke up. There was memory loss. And still, there are more questions than answers.

I’m writing to you from the waiting place. A place I know too well. I’ve waited here for her before—for release dates and clean drug tests, for good news from bad doctors, for phones that never rang, for the smallest sign she was finding her way back to herself. This is the place where I first learned what it means to love someone you can’t always trust, someone who says “I love you” even as they hurt you. And now that I have a son, the stakes are so much higher. I’m not just protecting myself anymore. It’s not just my heart on the line.

The thing I’m holding onto is that at least Mom’s awake. I am grateful. I am relieved. But still, the question lingers like smoke in a room no one wants to enter—why did this happen? Was it meth again, like it was six years ago? Or was it simply the long wear of a body that’s been in survival mode for too many years?

We’re waiting on test results. It’s only a matter of time.

I want to believe it wasn’t drugs. I want to believe she wouldn’t risk everything—not again. Not with my son hanging in the balance. But my mother used meth for forty years before she got sober. What do you think the odds are?

If it is the same old story, where does that leave me? I know I can survive it. I’ve survived worse. But I won’t let my son grow up inside the same grief I did. If I have to, I’ll place boundaries around their relationship. I’ll begin the slow, heartbreaking work of weaning him off her love. Because I will not let her break his heart the way she broke mine again and again.

I haven’t written about the morning it happened—the phone call, the way the color drained from my body, the way I had to keep it together because there were still guests in my house, still a child to care for, still breakfast to make. I’m avoiding that story because the fear rises when I try to approach it. I’m not ready. I’m still hosting. Still mothering. There’s no time to fall apart.

But I’ll write it. When I’m ready, I’ll take myself through the same process I created—the Fear to Flow framework—to write the thing I want to run from. That’s why I made it. Not for the easy stories, but for the ones that unravel you. For the truths that won’t leave you alone.

And maybe, like so many times before, the story will come—in the waiting.

For now, I’m driving toward the ocean. Toward Charleston. To listen to the waves and feel a power outside of myself. My son is asleep in the backseat, our dogs curled beside him. Outside the window, the Spanish moss sways like time made visible, spilling from the branches like strands of prayer. I keep looking for the great blue heron, the egret—those quiet, patient birds of the low country that remind me to go slow. To wait. To trust the hush between chapters. You don’t have to figure it all out today. The answers will come in their own time.

I don’t have a tidy monthly wrap-up for you this time. I’m tired. I’m grateful. I’m raw. I’m in the middle of it. Maybe you are, too. What I can say is this: if you’re in your own waiting place, let it be what it is. Don’t rush it. Don’t explain it away. Rest if you can. Let the tide do what it’s meant to do. Because even here, even in the ache, the stillness, the uncertainty, there is something holy about being exactly where you are.

I’ll tell the rest of the story soon. But for now, I’m whispering thank you to the trees, the sky, the sea. Even when it hurts. Even when I don’t yet understand what it all means.

Thank you for sharing. Helping others by putting your pain out there, making yourself vulnerable, publicly, to help others, has got to be one of the hardest things to do, and you do it creatively and powerfully. God bless you, your family, and everyone that reads this.

Bless you for sharing your heart and allowing words to heal your soul. My daughter also struggled with a meth addiction. She's been sober for a year now and I am so grateful for everyday. Her addiction rocked my world but as we slowly grow back together, things feel hopeful and much brighter. Baby steps.